100 years ago, the RMS (Royal Mail Steamer) Titanic tragically sank on her maiden voyage Sunday, April 14, 1912 after hitting an iceberg. 1,598 passengers and crew perished due to a combination of errors. Many books have been written, and movies made about this famous disaster, including the 1997 hit film “Titanic”.

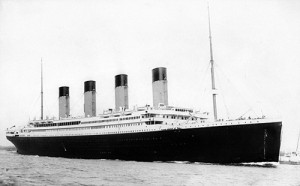

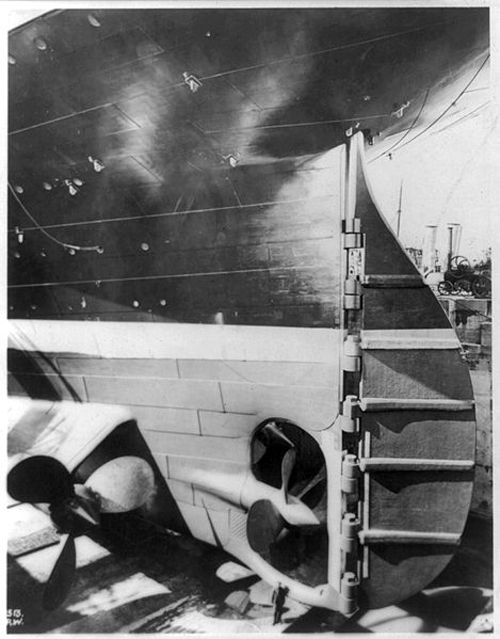

Titanic was the second of three Olympic-class ocean liners belonging to the England based “White Star Line”. Built as a transatlantic ocean liner, Titanic was 882 feet long and 92 feet wide, making her one of the largest ocean liners built at the time. Equipped with three propellers driven by two reciprocating steam engines on either side of a single steam turbine, the two reciprocating steam engines were 63 feet long and weighed 720 tons each. The center propeller could only go forward, while the two outer propellers could go in reverse if needed. Steam was made by 29 coal-fired boilers that had to be continuously manned by shifts of 176 crewmen.

Passenger facilities aboard Titanic were built to the highest standards. The ship could accommodate 739 first class, 674 second class, and 1,026 third class passengers. All three classes were segregated from each other by barriers consisting of doors and gates which were monitored by members of the crew. In those days passenger ship companies made a lot of money taking immigrants to the United States from Europe, most of these immigrants could only afford third class passage.

Dubbed as “unsinkable”, Titanic was divided into sixteen watertight compartments and was designed to stay afloat with four of them completely flooded. Designed to be able to carry up to 64 lifeboats, Titanic was only equipped with 20 lifeboats, which was the minimum number required by safety regulations at the time. The main lifeboats consisted of 14 wooden lifeboats which were 30 feet long by 9 foot wide. Two smaller wooden lifeboats and four “collapsible” lifeboats made up the rest. The collapsible lifeboats had heavy canvas sides which were designed to be raised before they were used.

Titanic was launched at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Ireland on May 31, 1911 and final fitting out was completed at the docks. Captain Edward Smith, the most senior captain of the White Star Line was put in command of the Titanic. Also assigned to the Titanic were seven other officers to help in running operations on the large ocean liner. At the last minute White Star management shuffled some of the Titanic’s officers. David Blair, then the second officer, was reassigned to another ship. In his hasty departure, he accidentally kept the only key to the storage locker containing the binoculars intended for the lookouts.

On Wednesday April 10, 1912 the Titanic left on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England with two stops in Cherbourg, France and Queenstown, Ireland to pick up more passengers before proceeding to New York City in the United States. Titanic was carrying 913 crew members and 1,316 passengers which was just over half of her full passenger capacity of 2,439. Some of the most prominent people of the day were onboard Titanic: millionaires John Jacob Astor IV and Benjamin Guggenheim, Macy’s owner Isidor Straus and wife Ida, millionaires Margaret “Molly” Brown, and film actress Dorothy Gibson to name a few. Joseph Bruce Ismay, who was chairman of the White Star Line and Titanic’s Chief Designer Thomas Andrews were also on board to observe any problems with the new ship.

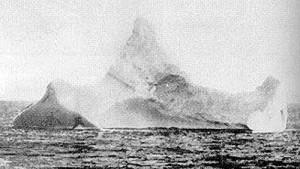

The evening of Sunday April 14 found the Titanic around 370 miles southeast of Newfoundland, Canada. The weather was very cold with clear skies, little wind, and icy conditions were starting to develop. Titanic had received several iceberg warnings during the day from other ships in the area. (An iceberg is a very large piece of ice that has broken off from a snow-formed glacier or ice shelf and is floating in the ocean). Although Captain Smith was aware of possible icebergs in the area, the Titanic’s speed was not slowed, and she continued to cruise at 25 mph, which was just short of her maximum speed.

Ninety-five feet above the Titanic’s deck, on the forward mast was the “crow’s nest” which always had two crewmen posted as lookouts. Around 11:39 p.m., look-out Frederick Fleet spotted an iceberg and phoned the bridge “iceberg right ahead.” First Officer Murdoch immediately reversed the engines and tried to steer the Titanic around the iceberg. Since the center propeller could not be reversed, it was simply stopped by the engine-room crew. This affected the water flow around the massive rudder reducing its effectiveness. The Titanic missed hitting the iceberg head-on, but the iceberg still scraped against the forward right side of the ship, causing some major leaks. The engines were stopped and the ship was allowed to drift while crewmen checked for damage, it was reported to the bridge that five forward compartments were flooding.

Thomas Andrews, was summoned to the bridge, and after hearing the damage reports, told Captain Smith that the Titanic would sink. At 12:05 a.m. Captain Smith ordered that the lifeboats be readied and that the passengers be brought to the main deck. First Officer Murdoch and Second Officer Lightoller were put in charge of loading the lifeboats. Many passengers and crew were reluctant to obey, either refusing to believe that there was a problem or preferring the warmth of the inside of the ship to the bitterly cold night air. There had never been a lifeboat drill for the passengers, and the crew had practiced launching the lifeboats just once. Captain Smith was now faced with the fact that there were far too few lifeboats to save everyone onboard.

Around 12:20 a.m., the loading of the lifeboats was started; many of the 14 main lifeboats were launched well short of their rated 68 passenger capacity. Few passengers at first were willing to get in the lifeboats and the officers found it hard to persuade them. One millionaire was heard to say: “We are safer here than in that little boat.” By 1:20 a.m., as the Titanic began to sink deeper into the water, the seriousness of the situation became apparent to the passengers who began saying their good-byes, with husbands escorting their wives and children to the lifeboats. Distress rockets were fired every few minutes to attract the attention of any ships nearby and the radio operators repeatedly sent distress signals.

It also became clear to those still on Titanic that there would not be enough lifeboats for everyone. Officers loading the lifeboats tried to make sure that only women and children were let into the lifeboats with a few members of the crew to run the boats. Some couples refused to be separated. Ida Straus, the wife of Macy’s department store owner Isidor Straus, told her husband, “We have been living together for many years. Where you go, I go.” They sat down in a pair of deck chairs and waited for the end. Benjamin Guggenheim changed out of his life vest and sweater into a top hat and suit declaring his wish to go down with the ship like a gentleman. Others panicked, such as when a group of passengers attempted to rush a lifeboat as it was being lowered. Fifth Officer Lowe fired three warning shots in the air from his pistol to restrain the crowd.

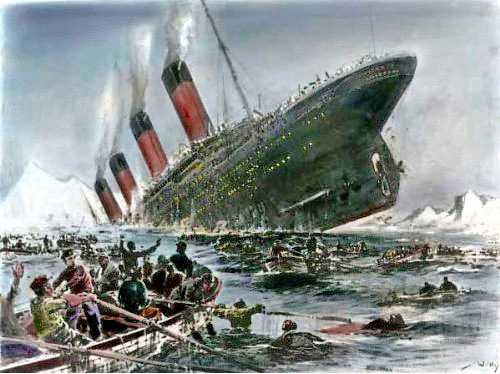

At about 2:15 a.m., Titanic’s angle in the water began to increase rapidly as water poured into the ship. Her suddenly increasing angle caused a giant wave to wash along the ship from the bow, sweeping many people into the water. Eyewitnesses saw Titanic’s stern lifting high into the air as the Titanic sank bow first. Survivor Jack Thayer recalled seeing “groups of the people still aboard, clinging in clusters or bunches, like swarming bees, only to fall in masses, pairs or singly,” as the great rear section of the ship, two hundred and fifty feet of it, rose into the sky to a nearly vertical 90 degree angle, where it remained for a few moments. Thayer reported that it rotated on the surface, “gradually turning her deck away from us, as though to hide from our sight the awful spectacle; then the Titanic slid quietly into the sea.”

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, hundreds of passengers and crew were left dying in the icy ocean, surrounded by debris from the ship. The water was deadly cold with a temperature of only 28 degrees F. People in the water slowly lost consciousness and began dying; those in the lifeboats were horrified to hear the sounds of people in the water screaming, yelling, and crying. Only a few of those in the water survived. Among them was Second Officer Lightoller, who made it to a capsized collapsible lifeboat. Around 35 men climbed on top of the upside down lifeboat and clung on precariously, trying to keep their balance while paddling slowly away.

Fifth Officer Lowe, in charge of one of the lifeboats, mounted the only attempt to rescue those in the water. He gathered together five of the lifeboats and transferred the occupants between them to free up space in his. Lowe then took a crew of seven crewmen and rowed back to the site of the sinking. By the time they arrived at the site of the sinking, almost all of those in the water were already dead and only a few voices could still be heard. They did find four men still alive, one of whom died shortly afterwards, otherwise all they could see were “hundreds of bodies in lifebelts”. Titanic’s survivors were finally rescued by the RMS Carpathia, which had steamed through the night at high speed and at considerable risk, as the ship had to dodge numerous icebergs. There were some scenes of joy as families and friends were reunited, but in most cases hope died as loved ones failed to reappear, 1,598 passengers and crew had perished in the sinking. Among the dead were Captain Smith, First Officer Murdoch, Thomas Andrews and many famous passengers. One notable survivor was Joseph Bruce Ismay, who was chairman of the White Star Line. Ismay was later heavily criticized by the press for deserting the ship while women and children were still on board.

RMS Carpathia arrived at New York City with all of the survivors on the evening of April 18 after a difficult voyage through pack ice, fog, thunderstorms and rough seas. Due to communications difficulties, it was only after Carpathia docked, three days after Titanic’s sinking, that the full story of the disaster became public knowledge. The prevailing public reaction to the disaster was one of shock and outrage: why were there so few lifeboats? And why did Titanic proceed into a reported icefield at full speed? Public investigations were set up in Britain and the United States. They reached similar conclusions: the regulations on the number of lifeboats that ships had to carry were out of date and inadequate; Captain Smith had failed to take proper heed of ice warnings; the lifeboats had not been properly filled; and the collision was the direct result of steaming into a danger area at too high a speed. The disaster led to major changes in maritime regulations concerning lifeboats and other safety measures.

On September 1, 1985 a joint US-French expedition led by Robert Ballard found the wreck of the Titanic. Numerous expeditions have been launched in the years since to film the wreck and salvage objects from the debris field that are on display in a traveling exhibit.

Picture of the Titanic, showing the rudder and the center and outer propellers. Note the man at the bottom of the picture.